Frank Sinatra and the reinvention of American popular song

Miles Davis once famously said, “If any artist wants to keep creating they have to be about change.” The illustrious jazz trumpeter may well have had Frank Sinatra in mind with that remark because between 1953 and 1964 Sinatra’s creativity changed the trajectory of modern recorded popular music and jazz.

Sinatra is a transformative artist and his 1956 album Songs for Swingin’ Lovers is a watershed moment in popular music. The remarkable string of popular albums that followed – on Capitol Records and later his own Reprise label – are simply transcendent.

There is a compelling backstory to Sinatra’s extraordinary achievement.

Scott Fitzgerald famously claimed, “There are no second acts in American lives.” But when it came to the 20th Century’s most accomplished singer of popular songs, Scott Fitzgerald was wrong. Because there are not many second acts to compare with Frank Sinatra's.

Throughout the 1940s, Sinatra was at the very pinnacle of popularity and fame, one of the world’s most popular and best-selling music artists . . . but by 1952 Sinatra’s career was on the brink of disaster.

His tempestuous marriage to Ava Gardner was floundering. He had lost favor with the public – the fans who’d once adored him had abandoned him. And when his wife Nancy Sinatra petitioned for a legal separation, an antagonistic press turned positively scathing.

How bad was it? Very bad. Sinatra was in serious financial difficulty. He couldn’t find work in Hollywood – in 1949 MGM let him go and in 1950 Universal Pictures refused to renew Sinatra’s option. When his record sales and chart success plummeted, he was dropped by Columbia Records. CBS cancelled his television show. He was unceremoniously released by his theatrical agency. And then to top it all, he lost his voice. Appearing at the Copacabana one night he opened his mouth to sing and nothing came out. He had suffered a vocal cord hemorrhage.

Frank Sinatra was down, but not quite out.

The celebrated James Jones war novel From Here to Eternity was being filmed in 1952 by Columbia Pictures and Sinatra saw an opportunity for redemption in the pugnacious character of Angelo Maggio. He won the role and was awarded the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his performance, giving a kick-start to his career revival.

The second key piece of Sinatra’s comeback fell into place when on March 13, 1953 Sinatra met with Capitol Records Vice-President Alan Livingston and signed a recording contract. At Capitol Sinatra teamed with a brilliant 32 year old arranger named Nelson Riddle and together they began to reinvent the form and format of American popular song.

The early 1950s saw a new musical format replace the phonograph record – the 12” long playing album. Sinatra mastered this new format with his innovative idea of the “concept album” linking together each song in the album by musical similarities and emotional qualities.

At about the same time, the end of the “Big Band era” of the 1930s and 40s saw a stable full of the finest jazz musicians all show up in Hollywood and go to work in the recording studios.

So we have a lively, eager to prove themselves new record company, the emergence of the long playing album, a musical genius named Sinatra, a brilliant young orchestrator Nelson Riddle, and their pick of all the very best jazz musicians in the world. The stars were aligned.

Beginning in 1954 and ’55 with the paired releases of Songs for Young Lovers and In the Wee Small Hours, Sinatra began setting the stage for the arrival of a new exuberant musical genre. These two albums established a template for his future recordings. He would alternate albums of swinging up tempo songs followed by albums featuring poignant songs of loss and longing.

But it’s the release of Songs for Swingin’ Lovers in 1956 that created the biggest explosion. A huge popular success Sinatra and Nelson Riddle introduced the public to a new kind of swinging jazz sound and style. Modern. Contemporary. And very hip.

Songs for Swingin’ Lovers is a singular achievement that changed the trajectory of modern popular music. With this album Frank Sinatra changed our aesthetic taste and he changed how we listen to a singer. If high art is defined by its artistic merit, innovation, and ability to evoke a profound emotional response, then Songs for Swingin’ Lovers qualifies.

With the seminal song off the album Sinatra and Riddle managed to create an indelible piece of popular music. On January 12, 1956 Frank Sinatra walked into KHJ Studios in Hollywood and recorded a Nelson Riddle arrangement of Cole Porter’s I’ve Got You Under My Skin. Sinatra’s reading of the Porter classic is one his most celebrated and acclaimed performances. In the long history of American popular music there are few achievements that reach the realm of musical genius. Sinatra’s I’ve Got You Under My Skin is one of them.

As the story goes the song was a last minute addition to the album. Rushed for time and with Sinatra’s “I want a long crescendo” instruction in mind, Riddle frantically wrote the arrangement in a taxi cab on the way to the studio. No, seriously! Riddle’s iconic arrangement was penned in a cab on the way to the studio.

Rushed or not, it is one of the two or three most electrifying pieces Riddle ever wrote. A wildly exciting burst of Bolero like fireworks highlighted by Milt Bernhart’s rowdy, wild trombone solo. As a young man Nelson Riddle heard Serge Koussevitsky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra perform Maurice Ravel’s Boléro and he never forgot the experience. It’s for sure that with I’ve Got You Under My Skin he designed a signature Riddle take on the famous Bolero motif.

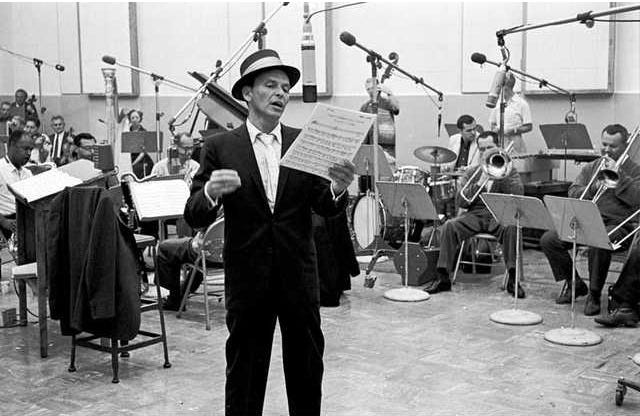

Sinatra recorded live. Live in the studio that was Sinatra in his element . . . loosened tie, fedora angled, microphone positioned, sheet music on a stand, situated right next to the rhythm section with the orchestra arrayed around him . . . he would lay down two or three tracks over the course of several hours. That’s the mental picture we have of Sinatra recording I’ve Got You Under My Skin. It took twenty-two takes to satisfy Sinatra but the result is one of the greatest pieces of music ever put to wax.

The bell-like sound of a celesta in the opening sets the tone for a finger popping Nelson Riddle vamp – a foundation motif figure repeated Bolero-like throughout. Sinatra’s carefree entrance is pure insouciance.

I've got you under my skin

I've got you deep in the heart of me

So deep in my heart that you're really a part of me

Riddle establishes a marvelous instrumental tension around Sinatra’s vocal line adding a baritone sax and then ratcheting up the slowly building tension by adding sustaining strings to the vamp figure as Joe Comfort’s bass sets the tempo.

Against the controlled pressure-building tension of Riddle's orchestration Sinatra delivers the first chorus. His phrasing has a rhythmic dimension – here how he pronounces “affair” and to the way his phrasing contributes to the stanza’s rhythmic organization. Sinatra has an impressionist way of extending the phrasing of words that phonetically suggests the sound it describes – dig his delivery of the word “under.”

Sinatra wanted an extended crescendo and Riddle designed a dynamic tension filled Bolero-like roller coaster ride. That insistent vamp figure gradually gathering steam as greater instrumentation is added . . . building and building then, at the peak of the tension, exploding with Milt Bernhart’s raucous breakout trombone solo. Bernhart is right on the edge of musical chaos in an orgy of what Will Friedwald, the great analyst of Sinatra's work, calls, "Atavistic off-the-chord energy."

Irv Cotler’s drums pave the way for Sinatra’s return at the release as he drives things to even more frenetic heights delivering a deliciously swinging, “I would sacrifice anything.”

Continuing to build excitement he explodes with energy, “In spite of a warning voice that comes in the night/and repeats, how it yells in my ear.” And then, bending the note on “don’t” Sinatra simply brings the house down as his voice soaring, “right inside you,” he thunders.

Don't you know, little fool, you never can win?

Why not use your mentality?

Step up, wake up to reality

But each time I do, just the thought of you

Makes me stop just before I begin

On “begin,” the music briefly stops and Sinatra, sotto voce, lowers the tone as the celesta returns, he delivers the closing lines and Joe Comfort’s walking bass fades out the coda.

‘Cause I’ve got you under my skin

Yes, I’ve got you under my skin.

The music critic and author Mark Steyn wrote that, reconstructed by Sinatra and Riddle I’ve Got You Under My Skin “emerges as the apotheosis of the Cole Porter songbook, a glorious combination of passion and rhythm.”

Indeed.

CODA

Sinatra had an artistic affinity for Cole Porter songs. He recorded the definitive reading of so many Porter compositions. A Cole Porter song in Frank Sinatra’s hands was . . . well, nothing less than musical magic.

Cole Porter wrote the song for Born to Dance, a 1936 film starring Eleanor Powell and James Stewart. In the film Stewart sings the wonderful Porter ballad Easy to Love. Featured in a nightclub scene I've Got You Under My Skin was danced to by the duo Georges and Jalna and later sung for the first time ever by Virginia Bruce to Jimmy Stewart.

It was nominated for an Oscar but lost to the Jerome Kern/Dorothy Fields classic, The Way You Look Tonight. (What an era for music the 1930s was!)

In writing the arrangement Riddle referenced Ravel’s Boléro but also Stan Kenton’s recording 23 Degrees North, 82 Degrees West with its wild overlaid layered trombones which gave him the idea for the Bernhart solo.

Nelson Riddle's work on the song may be the all-time great pop vocal arrangement, and certainly Milt Bernhart's 16-bar contribution is the most-heard trombone solo in recorded music.

The band knew this Riddle arrangement was special. They sat stunned for a few seconds after the first run through rehearsal . . . then stood up and applauded.

Sinatra arrived in the studio, recorded two songs for the album, and then turned to I've Got You Under My Skin. A number of takes and Sinatra knew this was different. Extraordinary. He intended to get it just right. A few more takes refining things, then still struggling for perfection several more.

Milt Bernhart was nearly out of gas, exhausted when Sinatra decided the trombonist needed to be closer to the mike so he could, in Sinatra’s words, “blow the roof off.” But the mike was too high above the trombonist. So Sinatra himself went and found an “apple” box for Bernhart to stand on. That was all it took. By that 22nd take, they had perfection.

Recorded nearly seventy years ago the Sinatra-Riddle-Bernhart record of I've Got You Under My Skin will still be heard in another seven decades. And, to paraphrase Mark Steyn, you can bet that most every night between now and then in some joint somewhere or other some wannabe-Sinatra will be singing that arrangement or his approximation thereof, hoping to deflect just a little of its sheen his way.